Entlarvung der mutierten Gene hinter Hirnaneurysmen

[ad_1]

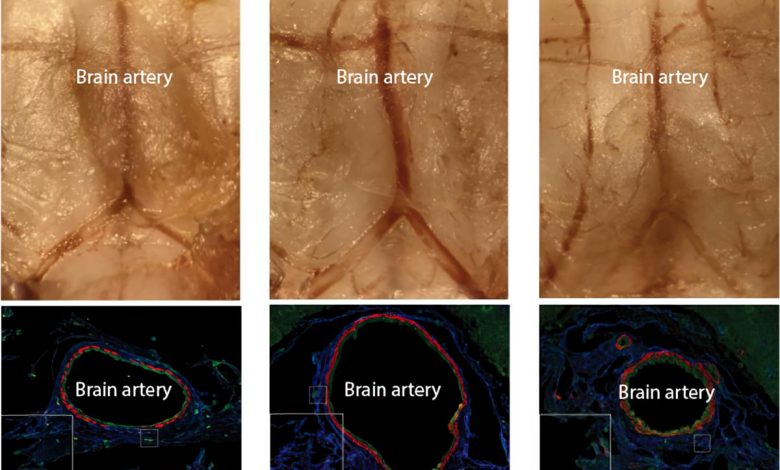

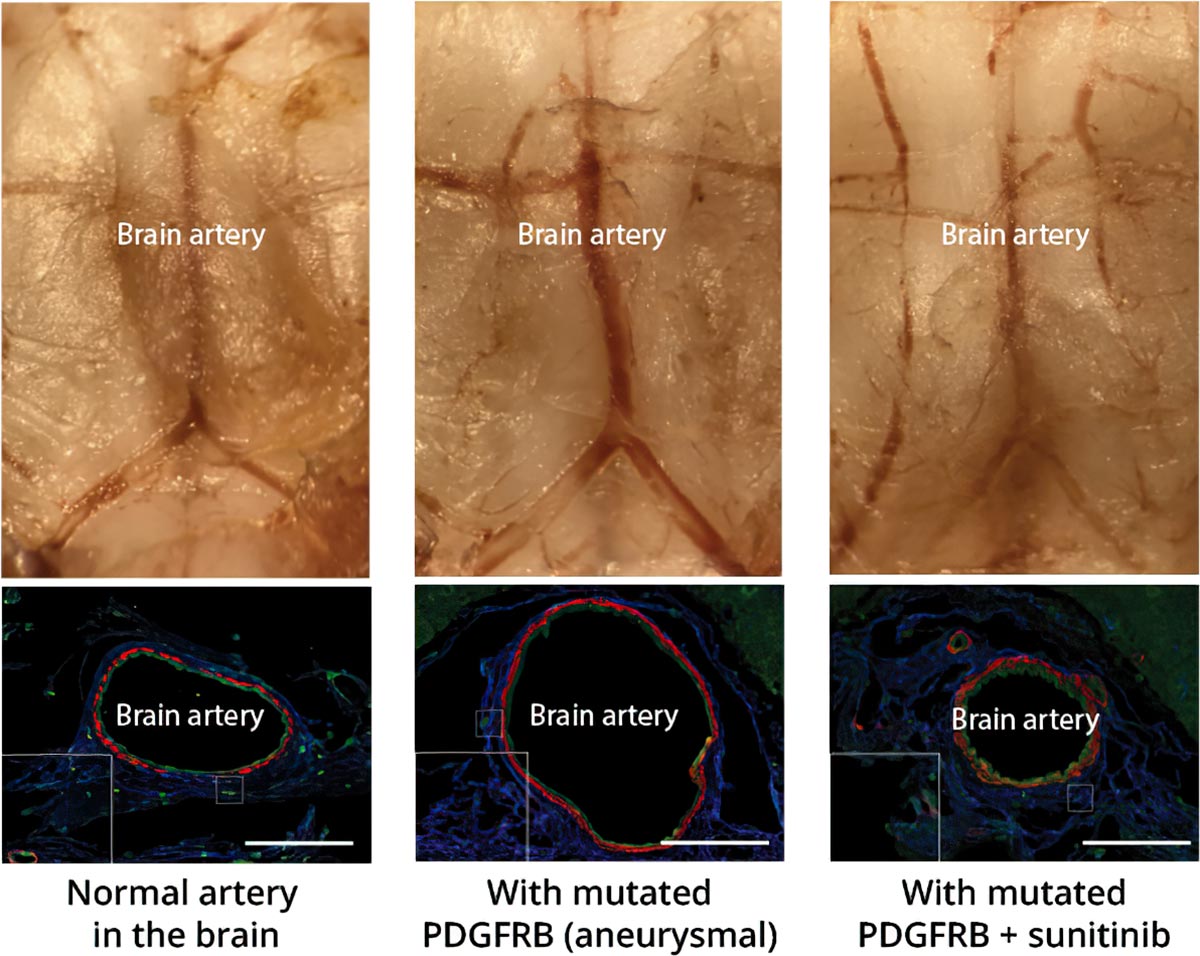

Ein Mausmodell eines intrakraniellen Aneurysmas und einer erfolgreichen medikamentösen Behandlung. (Links) Ein Foto einer normalen Basilikumarterie im Gehirn einer Maus oben und ein Querschnitt unten. (Mitte) Eine aneurysmatische Basilikumarterie, die sich auf den doppelten Durchmesser aufgebläht hat. Das Aneurysma entstand in dieser speziellen Arterie durch die Injektion eines Virus in der Nähe, der das entdeckte mutierte PDGFRB-Gen trug. (Rechts) Die Behandlung mit dem Medikament Sunitinib blockiert die abnormale Aktivität des mutierten Gens und kann so das Aneurysma verhindern. Bildnachweis: RIKEN

Forscher am RIKEN Center for Brain Science (CBS) in Japan haben eine Reihe verwandter Mutationen entdeckt, die zu intrakraniellen Aneurysmen führen – geschwächten Blutgefäßen im Gehirn, die jederzeit platzen können. Die Mutationen scheinen alle auf denselben biologischen Signalweg zu wirken, und die Forscher berichten über die erste pharmazeutische Behandlung, die durch die Blockierung dieses Signals funktioniert. Die Studie wurde am 14. Juni in Science Translational Medicine veröffentlicht.

Etwa 5 % der Bevölkerung haben unversehrte intrakranielle Aneurysmen in Blutgefäßen auf der Oberfläche des Gehirns. Obwohl es sich bei intrakraniellen Aneurysmen um aufgeblähte Arterien mit geschwächten Wänden handelt, bleiben sie oft unentdeckt – bis ein Bruch zu tödlichen Blutungen rund um das Gehirn führt. Selbst wenn sie im Voraus erkannt werden, ist die einzige derzeit verfügbare Behandlungsoption eine Operation, die ihre eigenen Risiken birgt, insbesondere wenn sich das Aneurysma an einer empfindlichen Stelle befindet. Die Suche nach anderen, nicht-chirurgischen Optionen hat daher hohe Priorität, und die Erforschung der Entstehung intrakranieller Aneurysmen hat das RIKEN CBS-Team zu einer solchen möglichen Behandlung geführt.

Intrakranielle Aneurysmen gibt es tatsächlich in zwei Arten: intrakranielle fusiforme Aneurysmen (IFAs) und intrakranielle sackuläre Aneurysmen (ISAs), wobei es sich bei etwa 90 % um die ISA-Variante handelt. Frühere Untersuchungen berichteten über Mutationen in IFA-Arterien, die Ursprünge des häufigeren ISA-Typs bleiben jedoch unklar. Um dieses Problem anzugehen, sequenzierte das RIKEN-Team die gesamten Exome – alle proteinkodierenden Teile davon[{” attribute=””>DNA— in cells that made up 65 aneurysmal arteries and 24 normal arteries. Along with subsequent deep-targeted sequencing, they found that six genes were common among IFAs and ISAs and never appeared in non-aneurysmal arteries, while 10 others appeared only in either IFAs or ISAs. While several factors, such as age, hypertension, and alcohol consumption, increase the risk of intracranial aneurysms, project leader Hirofumi Nakatomi from RIKEN CBS notes, “the unexpected finding that greater than 90% of aneurysms had mutations in a common set of 16 genes indicates that somatic mutation could be the major trigger in most cases.”

Further testing showed that mutations to all six of the genes common to IFAs and ISAs triggered the same NF-κB biological signaling pathway. The next step was to learn more about the mutations and try to block the abnormal signaling. First, they showed that mutations to one of the six genes, PDGDRB, could be traced along different layers within samples of human aneurysms. Then, after linking the PDGDRB mutation with faster cell migration and inflammation in cultured cells, they discovered that these effects could be blocked with sunitinib, a drug that prevents the changes to PDGDRB that allow signaling.

Next, they created a mouse model of intracranial aneurysm by using an adenovirus to insert mutant PDGFRB into the basilar artery at the base of the brain. After a month, the size of the artery had doubled in diameter and become very weak. As in the cultured cells, the effect of the mutant gene was blocked when the mice were given sunitinib; their basilar arteries remained normal-sized and strong. “Establishing the first non-surgical animal model of intracranial aneurysm is in itself an achievement,” says Nakatomi, “but more importantly, we suppressed artery expansion with a drug, indicating that intracranial aneurysms can be pharmacologically treated.”

Additional research will be required to demonstrate that this kind of drug treatment is effective for human patients. But perhaps the more difficult hurdle will be detection. As Nakatomi explains, “Unruptured intracranial aneurysms are usually detected by Magnetic Resonance Angiography or Computed Tomography Angiography during health checkups. If these tests are not available, then aneurysms are undetectable until they burst.” In Japan, where this research was conducted, many people can receive these tests as part of their annual health checkup, making the development of drug treatments particularly useful.

Reference: “Increased PDGFRB and NF-κB signaling caused by highly prevalent somatic mutations in intracranial aneurysms” by Yasuyuki Shima, Shota Sasagawa, Nakao Ota, Rieko Oyama, Minoru Tanaka, Mie Kubota-Sakashita, Hirochika Kawakami, Mika Kobayashi, Naoko Takubo, Atsuko Nakanishi Ozeki, Xiaoning Sun, Yeon-Jeong Kim, Yoichiro Kamatani, Koichi Matsuda, Kazuhiro Maejima, Masashi Fujita, Kosumo Noda, Hiroyasu Kamiyama, Rokuya Tanikawa, Motoo Nagane, Junji Shibahara, Toru Tanaka, Yoshiyuki Rikitake, Nobuko Mataga, Satoru Takahashi, Kenjiro Kosaki, Hideyuki Okano, Tomomi Furihata, Ryo Nakaki, Nobuyoshi Akimitsu, Youichiro Wada, Toshihisa Ohtsuka, Hiroki Kurihara, Hiroyuki Kamiguchi, Shigeo Okabe, Masato Nakafuku, Tadafumi Kato, Hidewaki Nakagawa, Nobuhito Saito and Hirofumi Nakatomi, 14 June 2023, Science Translational Medicine.

DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abq7721

[ad_2]

Source link